|

|

Welcome to the Tornado Page!

|

|

| Homepage | |

| Concept Map | |

| Curriculum Web | |

| WebQuest | |

| Hurricane | |

| Earthquake |

What is a tornado?

A tornado is a violently rotating column of air that descends from a thunderstorm. No other weather phenomenon can match the fury and destructive power of tornadoes. They can destroy large buildings, lift 20-ton railroad cars from their tracks, and drive straw and blades of grass into trees and telephone poles.

How do tornadoes work?

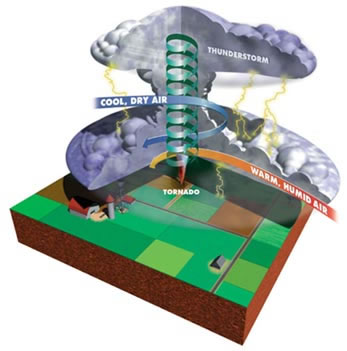

In order to form a tornado, you need three very different types of air to come together in a particular way:

Near the ground, there's a layer of warm, humid air and strong south winds. In the upper atmosphere, you'll find colder air and strong west or southwest winds. The air near the surface is much less dense than the cold, dry air aloft. This condition is called instability. It means that if the warm, moist air can be given an initial push to move upwards, the air will keep on rising, sending moisture and energy to form a tornado's parent thunderstorm.

The second ingredient is a change in wind speed and direction with height, called wind shear. This is linked to the eventual development of rotation from which a tornado may form.

The last thing you need is a layer of hot, dry air between the upper and lower layers. This middle layer acts as a cap and allows the warm air underneath to get even warmer and make the atmosphere even less stable.

When a storm system high in the atmosphere moves east and begins to lift the layers, it begins to build severe thunderstorms that spawn tornadoes. As it lifts it removes the cap, setting the stage for explosive thunderstorms to develop as strong updrafts form. If the rising air encounters wind shear, it may cause the updraft to begin rotating, and a tornado is born.

Where do tornadoes occur?

The U.S. has by far the most tornadoes in the world. It averages 1,000 tornadoes a year! Tornadoes also occur in other parts of the world, most notably in Australia.

The geography of the central U.S. is uniquely suited to bring together all the ingredients for tornado formation. With the Rocky Mountains to the west, the Gulf of Mexico to the south, and a terrain that slopes downward from west to east, this area has become know as "Tornado Alley," averaging more than 500 tornadoes annually.

During the spring and summer months, southerly winds originating from the Gulf of Mexico prevail across the plains, providing the warm, humid air needed to fuel severe thunderstorm development. Hot, dry air forms over the higher elevations to the west, and becomes the cap as it spreads eastward over the moist, Gulf air. Where the dry air and the Gulf air meet near the ground, a boundary known as a dry line forms to the west of Oklahoma. A storm system moving out of the southern Rockies may push the dry line eastward, with severe thunderstorms and tornadoes forming along the dry line or in the moist air just ahead of it.

Peak months of tornado activity in the U.S. are April, May, and June. However, tornadoes have occurred in every month and at all times of the day or night. A typical time of occurrence is on an unseasonably warm and humid spring day between 3 p.m. and 9 p.m.

When a storm system high in the atmosphere moves east and begins to lift the layers, it begins to build severe thunderstorms that spawn tornadoes. As it lifts it removes the cap, setting the stage for explosive thunderstorms to develop as strong updrafts form. If the rising air encounters wind shear, it may cause the updraft to begin rotating, and a tornado is born.

How are tornadoes measured?

Dr. T. Theodore Fujita ("Dr. Tornado") was a pioneer in the study of tornadoes and severe thunderstorm phenomena. In 1971, he created the Fujita Tornado Damage Scale to estimate tornado strength based on damage surveys. Since it's extremely difficult to measure tornado winds directly, this is the best way to classify them.

The scale goes up to F5 — or up to 318 mph. It's possible that a tornado could generate winds above the scale, but it has never been recorded. On May 3, 1999, an Oklahoma University Doppler radar remotely sensed tornado wind speeds above ground of 318 mph at Bridge Creek, Oklahoma — the highest winds ever found near Earth's surface, and right at the threshold of being F6 winds.